How I Discovered Stanford's Jewish Quota

Stumbling my way through the admissions archives

Welcome to Making History, a newsletter that takes readers beyond the page, outside the footnotes, and into the archive to show how historians reconstruct the past, and rediscover the present. This is history not as it is usually consumed — a finished product with the rough edges sanded away — but as it is produced. You can subscribe here. It’s free!

When you walk into the admissions archives you expect to read a lot about Jews.

Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Dartmouth, Williams — from the 1920s to roughly the 1950s all of these colleges had quotas on the total number of Jews allowed in each freshman class, and that’s just the schools that have had books written about them. (Congrats to Penn! Maybe the only Ivy League exception.) But other than a few preliminary sketches, which suggest Stanford never practiced a Jewish quota, and a few rumors about quotas at the university in the 1960s, nothing has been written about the history of admissions at the institution that witnessed the most dramatic rise in academic prestige in the twentieth century. The only comment on the subject from Stanford’s admissions office that I have been able to find states that, despite significant internal research, any suggestions that a Jewish quota was practiced at Stanford rests on the unsubstantiated “convictions” of a small number of alumni.

Either the admissions office was lying, or else they didn’t look that hard. While in my own work I admittedly almost missed the sole document that appears to have recorded the implementation of a Jewish quota at Stanford, it’s not as if it would have been that hard to find if the university had put a few staff members to work. The document is still there in the archives, waiting patiently in a folder marked “Admissions 1952-1953.”

I know this because almost exactly six years ago I arrived at the Stanford University archives to begin the initial work on what became my dissertation, now book project, “Meritocracy in America,” a history of meritocracy in higher education, Silicon Valley, and the Democratic Party.

I planned to spend a month looking at the vast collection of Apple’s records that Steve Jobs had sent over when he returned to the company in 1997 and decided the new Apple he intended to build would be so forward-looking it could get rid of its museum. I had written up an entirely speculative plan for the dissertation that suggested I’d (somehow) find a way to track connections between meritocracy in business, education, politics, and ideas. Surely, I reasoned, it couldn’t be an accident that so many people across different domains seemed to use the competition for college admissions as a kind of rationale for the rise of inequality writ large. Wiser minds politely noted that I’d never be able to get my hands on the materials that might substantiate this idea. I was dense enough not to take the hint, and inexperienced enough to think: Why not try?

Still, by the time I got to the Stanford archives, I assumed there was no way they’d show me the admissions files. There was a notable collection of records from the admissions department, but it was marked — in all caps, as I recall, unlike all the other collections — ‘RESTRICTED’. The archives of various Stanford presidents also had files on admissions, but access to these, too, was restricted until approved. I was so intimidated that at first I didn’t even bother to ask if the files might be opened.

Most of the books that had been written about admissions ran out of a paper trail in the 1950s for a reason: universities wouldn’t let researchers in. Many institutions had long had fifty-year rules about access to their records, but because FERPA required the protection of all student records as long as the former student was alive these rules had been extended to seventy-five years, sometimes longer.

Eventually, after a week or so spent looking at the Apple papers, I worked up the courage to ask about the admissions files. I expected to be shot down immediately. Instead, the university archivist carefully went through every folder, pulling FERPA protected material, and letting me see the rest. Stanford, I eventually learned, is much less concerned about the dangers of the past than its academic peers. (“We don't need any history,” as Wallace Stegner quoted one Silicon Valley executive; it might be more apt to say, given Stanford’s approach to its records and the other Silicon Valley materials available in the archives, “We don’t fear the past.”) Rather than seventy-five or fifty years, files at Stanford are made available twenty years after a president retires. I would eventually be allowed to work with admissions-related material from as late as 1991.

What I found when the archivists started bringing me boxes was a lot of Jews. The word seemed to be written on everything. And in all caps! A letter from a donor trying to get a friend’s son into Stanford? “JEWS.” New data on rising test scores? “JEWS.”

I distinctly remember thinking to myself, This is going to be so easy. (Never mind what any of this might tell us about meritocracy that was new.) But the closer I looked, the more confused I became. It seemed like “JEWS” was written — handwritten no less — on almost everything. The man in charge of admissions for most of the 1950s and 1960s, I learned, was a kind of caricature of a WASP: a bow-tied, potato-headed child of Congregationalists, who had studied the British empire for his PhD at Stanford before becoming a professor and, eventually, the first dean of admissions. For some reason every time I said his name, my girlfriend at the time, who was Jewish, couldn’t help but cackle at the sheer WASP-iness of it. Readers, meet Rixford Snyder.

Still, why write “JEWS” on nearly everything? “We must put a ban on the Jews,” a Yale official had advised his fellow Ivy League administrators, though one not “obvious on its face,” as Harvard’s president had put it. To find these quotes required previous historians to dig through box after box of materials, and that was back in the more indiscreet 1910s and 1920s. I was looking at Stanford material from the 1950s and 1960s, a time when the Jewish quota back east had begun to be significantly curtailed, and anti-Semitism in general in the US had begun its rapid postwar decline. (‘Anglo-Saxonism’ being displaced by a new invention, the ‘Judeo-Christian tradition’.) Still, these Stanford bureaucrats all seemed to have JEWS-addled minds.

Maybe I’m a bit slow, or maybe I was just learning how to work in the archives, or maybe this is how everyone figures things out. At some point I came across a document with JEWS written in all caps, but this time the scrawl noted, “See JEWS to Snyder.”

Huh. At that time Stanford was a much smaller school, with a very intimate administration — essentially all the documents I was looking at were routed through the office of President Sterling, or as everyone referred to him, Wally. Yet there on every document was the president’s full name. I did a double take. Here it was, the apparent origins of what I had supposed to be Stanford’s rampant mid-century anti-Semitism. ‘JEWS’ was short for another classic WASP, the son of a Methodist minister, President J.E. Wallace Sterling.

Eventually I came across another document, this one from 1969, that appeared to exonerate ‘Rixie’ — as his friends called Snyder — from whatever remaining doubts I had. (The ‘Rixie Fund’ that Snyder established has granted more than forty scholarships to his favored constituency, Stanford athletes.) As this document records, when Snyder was asked about rumors of a Jewish quota at Stanford, he responded that the admissions department had kept a single thin file since the late 1940s that was marked “Racial Discrimination – lack of at Stanford.”

The file contained statistics that appeared to show that though Stanford had a lower proportion of Jewish students than its eastern peers, this was because there were a quarter as many Jewish-Americans on the west coast as on the east coast. If anything, Snyder insisted, his department had unfairly favored Jewish students because the chairman of the board of trustees, a Jewish lawyer from San Francisco, had advised him in the early 1950s that the best way to avoid accusations of anti-Semitism would be “never to have the top person rejected in a school Jewish and the bottom one taken non-Jewish.” (Top and bottom here being defined purely in academic terms.)1

I felt chastened by my earlier mistake. How could I have been so mean to poor Rixie! “NO!,” he insisted on another occasion when asked about the “myth” that Stanford used quotas.2 He must have been telling the truth. As I dug into the archives, Snyder’s story began to appear more rather than less plausible. I’ll get into this more in a later post, but the short version is that based on the research I had done at the time, and the initial work done by other historians, it appeared that Stanford in the 1910s and 1920s really was different from its eastern peers. Instead of a quota on Jews, the school, because of the whims of its founder, Jane Stanford, had been forced to put a quota on women — she didn’t want a school founded to honor the memory of her dead son to get too girly. In response to this demand, Stanford administrators independently invented many of the methods of selective admissions associated with the Jewish quota on the east coast — including the great weight placed on ‘character’ — but largely in order to select among its women applicants, not to exclude Jews. As I wrote up my initial account of the rise of selective admissions at Stanford, I quoted Snyder’s explanation about the lack of a Jewish quota and left it at that.

It was probably a year later that I figured out the truth. In the past historians would spend months or years in the archives, going through documents one by one, until their lungs gave out from the dust (this actually happened), or they ran out of money. Today most of us (with the exception of a few remaining Luddites) fly in, photograph more documents in a week or two than anyone could read in a lifetime, and then head back home to sort through the mess. (For my dissertation I photographed something like 150,000 pages and, if my tagging system is to be believed, read a little more than 16,000 of them.)

I try to read a little in the archive as I go, especially at first, when I’m struggling to figure out what threads are worth pursuing; I also try to spend the evening organizing everything, while the first rough impressions are still fresh. Either I was too exhausted to manage that, or I was on autopilot when I tapped the photo button on my iPad, turned the two pages of the following memo, and moved on. Whatever the reason, I almost missed the document that’s probably the closest I’ll come to a historical smoking gun — insofar as such a thing exists (a subject for another post) — in my career. (A transcription follows below.)

[A transcription:

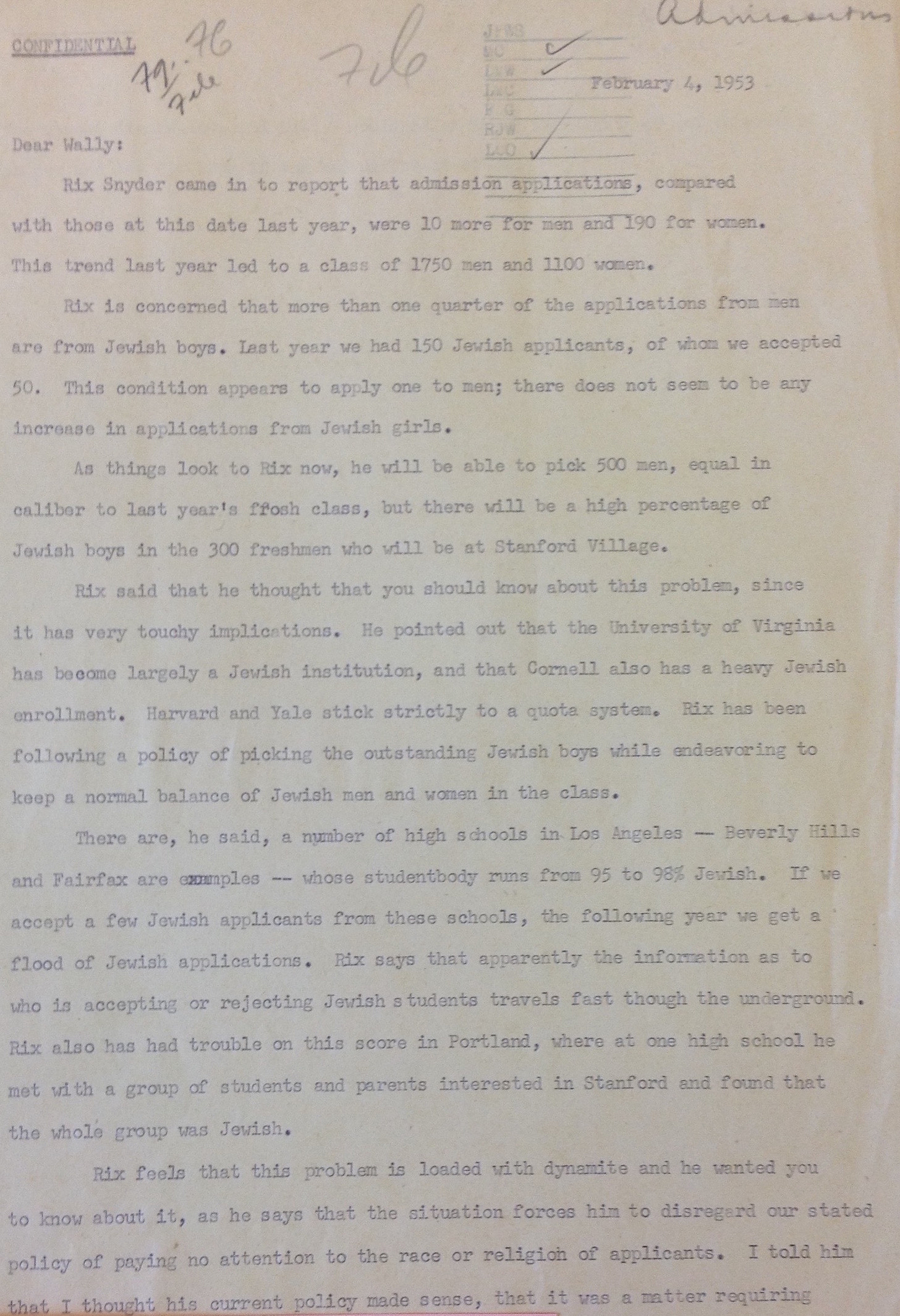

CONFIDENTIAL

February 4, 1953

Dear Wally:

Rix Snyder came in to report that admission applications, compared with those at this date last year, were 10 more for men and 190 for women. This trend last year led to a class of 1750 men and 1100 women.

Rix is concerned that more than one quarter of the applications from men are from Jewish boys. Last year we had 150 Jewish applicants, of whom we accepted 50. This condition appears to apply one [sic] to men; there does not seem to be any increase in applications from Jewish girls.

As things look to Rix now, he will be able to pick 500 men, equal in caliber to last year's fresh class, but there will be a high percentage of Jewish boys in the 300 freshmen who will be at Stanford village.

Rix said that he thought that you should know about this problem, since it has very touchy implications. He pointed out that the University of Virginia has become largely a Jewish institution, and that Cornell also has a very heavy Jewish enrollment. Harvard and Yale stick strictly to a quota system. Rix has been following a policy of picking the outstanding Jewish boys while endeavoring to keep a normal balance of Jewish men and women in the class.

There are, he said, a number of high schools in Los Angeles — Beverly Hills and Fairfax are examples — whose studentbody [sic] runs from 95 to 98% Jewish. If we accept a few Jewish applicants from these schools, the following year we get a flood of Jewish applications. Rix says that apparently the information as to who is accepting or rejecting Jewish students travels fast though [sic] the underground. Rix also has had trouble on this score in Portland, where at one high school he met with a group of students and parents interested in Stanford and found that the whole group was Jewish.

Rix feels that this problem is loaded with dynamite and he wanted you to know about it, as he says that the situation forces him to disregard our stated policy of paying no attention to the race or religion of applicants. I told him that I thought his current policy made sense, that it was a matter requiring the utmost discretion, and that I would relay these highlights of our conversation to you and let Rix know if you had different views.

FG]

Some background here: the author, ‘FG’, is Fred Glover, consigliere to the recipient, Stanford’s most important president, J.E. Wallace Sterling himself. Stanford Village was one of the university’s primary dormitory complexes: Snyder evidently believed more Jewish applicants would live on campus than off. In another report in the same year, Snyder had suggested that Stanford was losing many admitted students to other institutions because of its lack of dormitory space.3 It’s not too much of a stretch to suppose that he feared dorms filled with too many young Jewish boys would do still more to scare off his preferred clientele.

These two men, Glover and Sterling, may well have been the only ones to know about Snyder’s plan to implement a Jewish quota at Stanford. For the plan to have become public would have been particularly shocking because the Jewish quotas on the east coast were at just this moment in the midst of rapid decline, and Stanford was busily recruiting Jewish faculty in an attempt to increase its academic ranking. (The economist Kenneth Arrow, one of the school’s most successful young Jewish recruits, told me shortly before he died “My whole image of Sterling was certainly very different from that hinted here. … [The quota] must have been very subtle indeed if I didn't know about it.”) Sterling, Glover, and Snyder appear to have remained tight-lipped and unembarrassed even in private. Sixteen years later, in 1969, when questioned about rumors of a Jewish quota at Stanford, Glover advised Sterling, “I think our record is an excellent one.”

Was the Jewish quota of the 1950s and 1960s in fact a new policy? I still need to track down a few more statistics, but I later learned that Stanford’s annual reports from the 1910s to the 1940s included data on student religious affiliation. The key background fact about this data is that in the 1920s, because of the quota imposed by Jane Stanford, applications to Stanford for women were probably the most selective anywhere in American higher education. In this period, if you applied as a man at virtually any college, and you had the requisite high school coursework — and you weren’t Jewish — you were almost guaranteed admission. In 1925, for instance, the admission rate for women at Stanford was 14 percent, while the admission rate for men, which was unusually competitive, was 75 percent. For women applicants, importantly, selection at Stanford was performed not just by focusing on grades and the newly introduced intelligence tests but through “letters of recommendation from the alumni and friends of the University” as well as “many personal interviews.”

Although I haven’t tracked down any internal evidence clearly stating that ethnicity was a factor in selection in the 1920s, there turned out to be a straightforward tell in the statistics. From 1920 to 1933, the proportion of Jewish women enrolled at Stanford averaged 1.3 percent.4 In 1933, after a financial crisis brought on by the Depression led administrators to abrogate Jane Stanford’s gender-based quota and more than double female enrollment, the proportion increased to 3.8 percent. The average for the remainder of the decade remained 3.2 percent, nearly two-and-half times the proportion admitted in the selective era. Some kind of ethnic-based exclusion clearly had been at work.

Unlike the east coast schools, though, where the effects of the Jewish quota were far more dramatic (the proportion of Jewish students at Columbia was cut from around 40 percent to less than 20 percent), anti-Semitic exclusion at Stanford in the 1920s was a bit more subtle. And again unlike the east coast schools, where limits on Jewish enrollment remained in effect from the 1920s through the 1950s, at Stanford the practice appears to have fallen into abeyance with the elimination of most selective practices amid the financial exigencies of the Depression. As one dorm mother recalled of this period, Stanford was “taking every Tom, Dick, and Harry” who applied.5

A number of things changed after World War II, which led Snyder to introduce a new and apparently more deliberate quota on Jewish applicants. The rise of competitive college admissions is a subject for another post, but basically the 1950s and 1960s, the supposed heights of American economic egalitarianism, were also the crucible of a new and extraordinarily inegalitarian form of ‘meritocracy’ — there’s a reason that word was introduced in 1958, and why, although it was coined by an Englishman and initially greeted as definitively foreign, ‘meritocracy’ quickly became a new name for the American dream (or, for the New Left, nightmare). In brief, though, more students graduated from high school, and their parents had more money to send them to college, and students also proved willing to travel far greater distances in pursuit of institutional prestige. (The GI Bill, the typical explanation for these trends, is mostly a red herring.)

In no group were all of these developments more salient than among American Jews, who in the late 1940s applied to college at double the national norm (68 percent versus 35 percent). When applying to schools outside their home state, Jewish students were also admitted at less than half the rate of Protestants (63 percent versus 28 percent). Jewish students responded to these circumstances by essentially inventing the practice of applying to an endless series of colleges. In a period when the average Protestant student applied to 1.3 colleges, the average Jewish student applied to 2.2 colleges. In the late 1940s, when only 3 percent of all students applied to four or more colleges, 14 percent of Jewish applicants (and 17 percent of those with the highest grades) were submitting four or more applications. All of these disparities almost certainly increased in the 1950s.

Nonetheless, while all students increased their applications to college in the 1950s, and Jewish students more than any other group, the market for higher education remained a predominantly regional affair for much of the 1950s and 1960s. (The historian Lizabeth Cohen, a scion of mid-century Jewish New Jersey, once told me most students on the east coast hadn’t even heard of Stanford when she graduated from high school in 1969.) The largest increases in academic selectivity in US history occurred in the 1950s, but not until the end of the decade, after Snyder introduced his new Jewish quota. Moreover, the minimum SAT verbal score for admission to Stanford in the early 1950s was 375, well below the average of 500 of all SAT takers at the time, and roughly what officials believed would be the average if all high school students in the United States took the test. Even the median score for men was below the national average, between 450 and 500. (This is not to endorse the SAT as a valid measure of student ability; it was, though, a measure taken seriously by Snyder’s admissions office.) Finally, the acceptance rate in the early 1950s at Stanford was around 60 percent — no exact figure is available because, with the selectivity of the 1920s now a long ago memory, the admissions department was only beginning to standardize its internal statistics. In short, it was not as if WASP applicants at Stanford in the early 1950 were being squeezed out by an overwhelming wave of high-scoring young Jews.

The change that had occurred in the late 1940s and early 1950s, as Snyder observed in his travels to Los Angeles and Portland, was the mass immigration of American Jews to the west coast. In the 1920s, Jewish college students in the US were heavily concentrated in the northeast, with seven times as many students in the mid-Atlantic as in the western states. In 1935, for instance, 53 percent of all Jewish college students in the entire United States were enrolled in New York City. (This was why Columbia had been the first institution to introduce a Jewish quota.) In 1946, 50 percent of all Jewish college students were still in New York. By 1955, the figure had declined to 38 percent. In boomtown postwar Los Angeles, meanwhile, fully 13 percent of the 16,000 new immigrants arriving each month were Jewish. The city’s Jewish population increased from 130,000 in 1940 to 300,000 in 1951, and it kept growing. By the 1960s, Los Angeles had the third largest Jewish population in the world, behind only New York and Tel Aviv. (These figures all come from Deborah Dash Moore’s To the Golden Cities: Pursuing the American Jewish Dream in Miami and L.A., a must for Transparent fans.)

I don’t have the full statistics in front of me at the moment (if anyone has a PDF of this 1957 report on hand, please send), but suffice it to say that while the national percentage of Jewish students on the west coast remained small — increasing from 3.5 percent of all Jewish students in 1935 to 5.7 percent in 1955 — the increase in absolute numbers was more than enough to appear significant at the small number of prestigious west coast private institutions to which these students were disproportionately drawn.

Snyder, apparently with the president’s tacit approval — no record remains of how Sterling responded to the memo — held the line on Jewish students at Stanford nearly until the end of his career. In 1947, Jewish enrollment at Stanford was a little over 5 percent, and it stayed around 5 percent until 1965. This occurred even as the total number of students applying to Stanford almost quadrupled and the admissions rate was cut to around 25 percent. Where in 1954, 24 percent of male students and 35 percent of female students who enrolled at Stanford had been in the top 10 percent of their high school class, by 1961 the figures were 70 percent and 80 percent. One need not indulge in essentially anti-Semitic stereotypes about ‘smart Jews’ to note that, without a policy to exclude them, these conditions would typically have led to steady increases in Jewish enrollment. After the final end of the east coast Jewish quotas in the early 1960s, for instance, the average proportion of Jewish students at private universities increased to 18 percent.

Stanford’s Jewish quota was maintained without the more obvious machinery of student photographs or requests for mothers’ maiden names, which had been introduced at Harvard in the 1920s and had largely been eliminated by the 1950s. I interviewed two surviving admissions officers, John Bunnell and Douglas Walker, who had worked with Snyder as young men in the 1960s — yet another story for another time. (Let’s just say they lived up to the university’s ‘country club’ reputation: one had left to become an actual golf pro. Only one percent of admissions officers nationwide in the early 1960s were Jewish.) Even after I mentioned the memo above, leaving little reason to deny the use of a Jewish quota, both former officials said they hadn’t seen any evidence of discrimination against Jewish applicants. Perhaps they didn’t know, or perhaps old habits of discretion die hard.

Part of Snyder’s strategy was straightforward. President Sterling had asked Snyder in the early 1950s to begin heavy recruiting at east coast private high schools (Sterling’s own son attended Andover), and by the 1960s the admissions office was visiting 34 such schools each year in New England alone. Stanford officials, meanwhile, made no visits to New York’s selective public high schools. According to a particle physicist who sat on the admissions committee toward the end of this period, no recruiting was done at similarly Jewish-dominated schools in Philadelphia and Los Angeles.

It’s doubtful, however, that this is the whole story. As Snyder had himself explained, Jewish students didn’t need to be recruited to think about applying to a school like Stanford. A likelier explanation for how Snyder implemented his plan was simply that he exercised final authority in all admissions decisions. As one of his subordinates later explained, Snyder regularly admitted students from New England high schools without seeing their high school records; most turned out to be “bogos” — admissions office slang for students in the academic “bottom quarter” — but Snyder insisted he preferred a student like this because, in a characteristically WASP-y nautical locution, he “liked the cut of his jib.”

One Jewish student who attended Stanford in the 1960s was told by his high school guidance counselor that the university would only accept one Jewish student from each high school each year — he had been the one to get in. If this is true (and this student verified the claim from personal experience), it might offer an explanation for how Snyder implemented the suggestion, mentioned earlier, from the Jewish president of Stanford’s board of trustees. When Snyder wanted to admit a few Gentiles with less than stellar grades, he made sure to admit precisely one Jewish applicant near the top of the class.

However the quota was enforced, in 1966, after further inquiries from another Jewish member of the board of trustees, Snyder moved to increase the proportion of Jewish students at Stanford from 5 percent to 7 percent. There the figure appears to have stayed into at least the mid-1970s. This is somewhat surprising, as Snyder in 1969 was pushed out as dean amid the rise of the New Left — the founder of a draft resistance group was elected student body president and the president’s office was fire bombed. Snyder was replaced by a new dean, a working-class Irishman by the name of Fred Hargadon. Shouldn’t the proportion of Jewish students have risen faster after Snyder’s resignation? By the 1980s and 1990s, the proportion of Jewish students at Stanford stood at 10 to 12 percent, less than half that at Harvard, a third of that at Yale, and a fifth that at Columbia.

Regional demographics clearly account for some of these differences: California in the 1980s had 13 percent of the US Jewish population, while New York had 32 percent. But as a member of Stanford’s admissions office admitted in 1987, the rumors that the school had instituted a Jewish quota in the 1950s and 1960s, exactly the period when anti-Semitism was declining elsewhere in American higher education, had left a “lingering image … that Stanford is a ‘WASP-y’ university.” That image, at its inception at least, turns out to have been no accident.

What all this has to do with meritocracy may seem obvious. Just as with its peers on the east coast, Stanford’s claims to practice meritocracy were a sham at the beginning, just as they are a sham now with Asian students — a claim one could hear as early as the 1980s. What the Jewish quota actually reveals, at Stanford and elsewhere, can only be seen by rethinking how it relates to the origins of what we now know as ‘diversity’. That’s a story for another post (or an entire journal article). But perhaps the outlines of what I have in mind can be discerned in the following exchange between an angry parent of a rejected student and Snyder’s successor as dean in 1980. When the parent complained that Stanford’s “selection criteria are not consistently meritocratic,” the dean replied, “Our criteria are meritocratic, and that includes minority candidates as well as non-minority candidates. There is no one measure, and never has been, against which all candidates are ranked and admitted from the top down. As we say in our literature, excellence comes in many shapes and sizes and backgrounds.”6

The legacy of the Jewish quota is typically understood to be the way one form of exception to meritocracy, the exclusion of Jews, transitioned into another exception, the inclusion of Black, Latinx, and Native American students. The Jewish quota’s true legacy is how beliefs about merit that were always defined by race — in the initial case, the merits of whiteness — were redefined to include new ideas about race, only now under a new name, ‘diversity’.

To read that story, subscribe!

Thank you to the Stanford University Archives for permission to quote from and reproduce documents and images in their collections.

Rixford Snyder, “Comments on the Number of Jewish Students at Stanford,” May 21, 1969. Box 1C, Folder “Admissions (General) 69-70,” Pitzer papers, SC0218.

"Admissions Information," Series 1, Box 122, Folder "Committee to Study the Problem of Size as It Effects Stanford, 1966-70," Lyman Papers, SC0215.

This figure includes graduate students as well as undergraduates. but given the small number of women graduate students it shouldn’t be too skewed. I also exclude summer students because selective admissions were not practiced for the summer quarter.

Wow wow wow. My dad is Jewish, graduated from Beverly High in 1953 and matriculated at Stanford. We had read about this, but I had no idea how specific the evidence was

When I applied to Duke, in 1961, the first line on the application, even before your name, was "Religion". That probably saved them a lot of time in deciding who not to admit.