Everything We Know about the History of Diversity Is Wrong

And Historians Aren't Exactly Helping in the Harvard Case Currently Before the Supreme Court

Welcome back to Making History, a newsletter about how historians (or at least one historian) take the raw materials of the archives and turn them into the smooth narratives we otherwise take for granted. I’m Charles Petersen, a historian at Cornell University, a contributor to the New York Review of Books, and a senior editor at n+1 magazine. You may know me from my first post, “How I Discovered Stanford's Jewish Quota,” which led the university to issue a 75-page report and a public apology, covered widely in the national press.

In this entry, the first in a new series, I dive into the deep history behind the Harvard case currently before the Supreme Court. In the standard account, retailed repeatedly before the justices last October, “diversity” goes back to the Ivy League Jewish quotas of the 1920s. In this post, rather than uncovering a previously unknown episode in that story, I suggest some of the ways the already well-documented history of the Jewish quota can lead us astray. I then begin to outline a different story about where the idea of “diversity,” and the larger American approach to college admissions — not to mention “merit-based” assessment in business and elsewhere — actually comes from.

The entire academic industrial complex looks warily to the Supreme Court like some kind of malevolent god. The judgment has been coming for a long time. “Twenty-five years from now,” Justice Sandra Day O'Connor wrote in the landmark Grutter decision back in 2003, “we expect that … the use of racial preferences will no longer be necessary.” In 2014, a group calling itself Students for Fair Admissions, led by the conservative legal entrepreneur Edward Blum, filed a suit against Harvard to move that timeline up a decade.

In the initial district court briefs, Blum's group claimed that the use of “diversity” in undergraduate admissions was not a means for racial inclusion; diversity was, rather, a cloak for racial exclusion. Asian-American students are the alleged victims, their numbers having greatly increased at institutions like Caltech that claim to ignore race in admissions, while their numbers at Harvard have dramatically fallen. Harvard won the case at trial in 2019, a decision sustained by the First Circuit in 2020. In January 2022, the Supreme Court announced it would take the case on appeal (along with a related case at the University of North Carolina).

At hearings in October, it was not hard to divine the meaning of the judicial entrails. “Race for some highly qualified applicants can be the determinative factor” in admissions, Harvard's lawyer admitted, “just as being an oboe player” can be. “We did not fight a Civil War about oboe players,” Justice John Roberts, dark lord of moderation, retorted. “We did fight a Civil War to eliminate racial discrimination.”

Since only seven years ago in Fisher II (2016) the court affirmed the use of diversity in admissions in the strongest terms, the final decision in Students for Fair Admissions will clearly depend less on any new evidence than on the changing composition of the court. But if gerontocratic retirement decisions and undemocratic elections will determine the legal fate of diversity in college admissions, the conclusions of historians may yet prove crucial in the justices’ public reasoning.

Of the 505 paragraphs in the original Students for Fair Admissions complaint, more than 100 address the history of race in admissions.1 Harvard asked the trial judge to exclude this material from evidence; the judge refused, arguing that the use of race in admissions decisions was “especially sensitive” given past racial exclusion. As with so much of the politics of race in the United States, the ironies are rich: racial exclusion in the past may yet again prove to be the grounds for eliminating a program of racial integration in the present.

History is also one of the primary reasons Blum and his allies selected Harvard as a target. “Diversity” first emerged as a legal justification for the use of race in admissions as a result of Justice Lewis Powell's majority opinion in Bakke (1978), and Powell explicitly pointed to Harvard's admissions policy, the “Harvard Plan,” as his archetype. In an addendum to a 1977 amici brief, Harvard claimed that the university first began considering individual background rather than academic potential in selection decisions in order to admit a more “diverse” group of white students, such as “a farm boy from Idaho.” (As an Idaho native, I’ve always loved this particular detail.) Later, Harvard’s litigators claimed, the university had simply “expanded the concept of diversity” so that farm boys from Idaho were joined by “blacks and Chicanos and other minority students.”

Although this part of Powell's opinion was not joined by the majority, the diversity rationale embodied in the Harvard Plan was embraced by university administrators nationwide as a legitimized if not legally binding means by which to achieve affirmative action goals. In Grutter (2003), Justice Sandra Day O'Connor finally gave the use of diversity firm legal footing, again pointing to the Harvard plan as the model; president Biden's solicitor general has described the Harvard Plan as the national “benchmark.” Blum and his allies are only too happy to agree: the Harvard Plan should, they insist, be seen as the benchmark for the use of diversity in admissions. But in the original Bakke case, they argue, “the Supreme Court was misled,” and Grutter failed to grapple with the Harvard Plan’s “racist origins.” The correct decision today is then a straightforward syllogism: “If that benchmark is broken, then so is the precedent.”

In the account offered by Blum and his allies, the use of “diversity” in admissions began in the 1920s, when Harvard and other Ivy League institutions first set academic considerations aside to admit students on the basis of “geographic diversity” — those farm boys from Idaho. Behind the scenes, however, “geographic diversity” was just a cover for the real reason Harvard cared less about grades and test scores: the university had placed a quota on Jewish enrollment. Indeed, Jewish enrollment at Harvard did not just flatline due to the introduction of “diversity” considerations — the number of Jewish students dramatically declined. Farm boys from Idaho, thanks to the workings of “diversity,” then took the places vacated by boys from the Bronx. In recent decades, Blum et al continue, Asian-Americans, the “new Jews” in popular discourse, have become the “main victims” of the same methods of exclusion. Where before Idaho farm boys took the place of Jewish students, today African-Americans take the place of Asian-Americans. The “Harvard plan” of the 1950s, this line of argument concludes, was “the product of the most vile anti-Semitism,” and “Harvard is a recidivist.”

Historians should be especially attentive to these claims because they rest on a body of scholarship that we and our colleagues in historical sociology have produced. Since Alan Dershowitz and Laura Hanft turned to Martha Synnott's landmark account of Harvard's Jewish quota in their 1979 critique of Bakke, the findings of historians in the admissions archives have provided regular fodder for attacks on diversity.

Synnott's pathbreaking work was followed by a wave of scholarship examining anti-Semitism at almost every institution in the Ivy League. (Penn appears to be the lone exception.) These works typically chart a story from the 1920s to the 1950s, as the “Neanderthal” era of Jewish exclusion was replaced by a more enlightened approach. A second wave of scholarship added an ironic flourish by documenting how the judgments about diversity used to exclude Jews in the 1920s and 1930s were repurposed in the 1960s and 1970s as a way to include racial minorities. “Diversity,” the most influential account suggests, had “in the past had been used to limit the number of Jews”; only with this history occluded had “diversity” been “elevated by Powell's opinion to the status of a ‘compelling state interest.’”

Few of the historians who tracked the origins of diversity to this anti-Semitic genealogy argued that diversity considerations should be abandoned in our own time. Blum and his allies draw different conclusions. For them, the approach to diversity in college admissions that Powell made central in Bakke was not just a descendant of the anti-Semitic policies of the 1920s. Whether “geographical diversity” in the 1920s or “racial diversity” in the 1970s, this approach was a “continuation” of the same policy.

The specific language of “diversity” is key here because the word links the racially exclusive policies of the 1920s to the racially inclusive approach to admissions developed in the 1960s and 1970s. In the words of Justice Gorsuch during the oral argument in October: “In the 1920s [Harvard] wanted to impose a quota on Jewish applicants, but it didn’t want to do [it] through the front door, so it used diversity as a subterfuge for racial quotas.” A recent op-ed in the New York Times is blunter: “The very idea of ‘geographical diversity’ was invented to keep out Jews.”

As far as I know, the scholarly community has left this claim undisputed. The amici brief filed by members of the American Historical Association focuses entirely on the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, not the history of “diversity” or the background of Bakke.

But while there are continuities between the admissions practices of the 1920s and the 1950s, whether at Harvard or at other selective institutions, a closer examination of the record shows that the discourse of diversity is not among them. Jerome Karabel’s The Chosen, the dominant work to argue that diversity considerations originated with the 1920s Jewish quota, places the term “diversity” in quotation marks multiple times in descriptions of the admissions policies of the 1920s. This is the text that Blum and his allies repeatedly turn to for authority. The word “diversity,” however, does not appear in the sources Karabel cites.2 In my own reading in the admissions archives, I have not found a single instance where the term “diversity” or its cognates is linked with Harvard's Jewish quota. In those rare occasions where “diversity” appears in discussions about Jewish enrollment in the early twentieth century, the term is used to argue for the value of Jewish inclusion, not exclusion.

The claim that Harvard and other universities began pursuing a more national student body in the 1920s primarily as a mask for a quota on the number of Jewish students also does not withstand scrutiny. Rather, in the 1920s, as other scholars have argued in a literature unfortunately neglected in these discussions, the publicly stated aim of selective admissions procedures was not diversity but homogeneity.3 This aim was achieved: across the Ivy League, the 1920s saw reductions in enrollment both from Jewish boys from the Bronx and from farm boys from Idaho, with students from both the urban and rural working-class replaced by private high school graduates and alumni children (i.e. “legacies”).

Leading universities in the 1920s period did, it is true, promote policies to expand the geographic provenance of their students. But such policies were not new, nor were they closely related to the exclusion of Jews. “Even before the Civil War,” Harvard’s attorney noted in the oral argument in October, the university attempted to “diversify on … geography.” Instead of a cover for the Jewish quota, expanded national student recruitment in the 1920s was another episode in a longstanding project to turn universities into socialization centers for a unified, and socially uniform, national white business class. If anything, administrators feared that expanded national recruitment might accidentally bring in additional Jewish students. Some of those Idaho farm boys might turn out to be Cohens. This is why, in a coincidence completely unremarked in the standard scholarship, many of the strongest opponents of the Jewish quota at Harvard in the 1920s were also strong proponents of expanding the geographic origins of the student body.

There are, it is also true, important continuities between the student selection methods promoted in the 1920s and those made use of under the heading of “diversity” in the 1950s, the 1970s, and the 2020s. Above all, the 1920s witnessed a growing emphasis in admissions decisions on students’ personal qualities. But if such judgments increased in the 1920s, their origins extend far beyond the exclusion of a single ethnoracial group, and, indeed, far beyond Harvard, the Ivy League, and university administration, into large-scale transformations in the business world, government bureaucracy, the social sciences, and the entire US political economy.

This is not to say that these transformations in early twentieth-century American society — let alone college admissions policy — had nothing to do with race. In a white supremacist society, whose most “progressive” elements found in Jim Crow a happy marriage of advanced government regulation and cutting-edge science, the maintenance of racial hierarchy can be found at the core of essentially any significant social development. But if the student characteristics sought by universities were deeply inflected by race, such qualities were no straightforward cover for the exclusion of a single group. Simple cover stories rarely carry much social legitimacy, because they are not that hard to see through. Instead, as the great Jewish-American writer Alfred Kazin remarked of his own indoctrination into the values of the WASP world in the 1920s and 1930s, “I was awed by this system, I believed in it, I respected its force.”

It is the deep and widespread social dominance of WASP cultural values, and in particular an ascendant faith in the importance of personalistic judgments as a balance to the fearsome new mechanism of test scores, that accounts for the power of the new approaches to “merit-based” selection across early twentieth century American society. The widespread nature of these values and this selection system also explains why, as I discussed in my first post, Stanford independently moved to introduce highly personalistic admissions procedures in the 1910s and 1920s, even though the university had next to no Jewish applicants. As my research over the past year has uncovered, the personalistic methods of student assessment that became widespread in the 1920s — not just at elite institutions but in more than two-thirds of US colleges and universities4 — find their proximate origins not in anti-Semitism but in the personnel movement in business, the vocational education movement in high schools, the new industrial psychology, and the World War I–era US military.

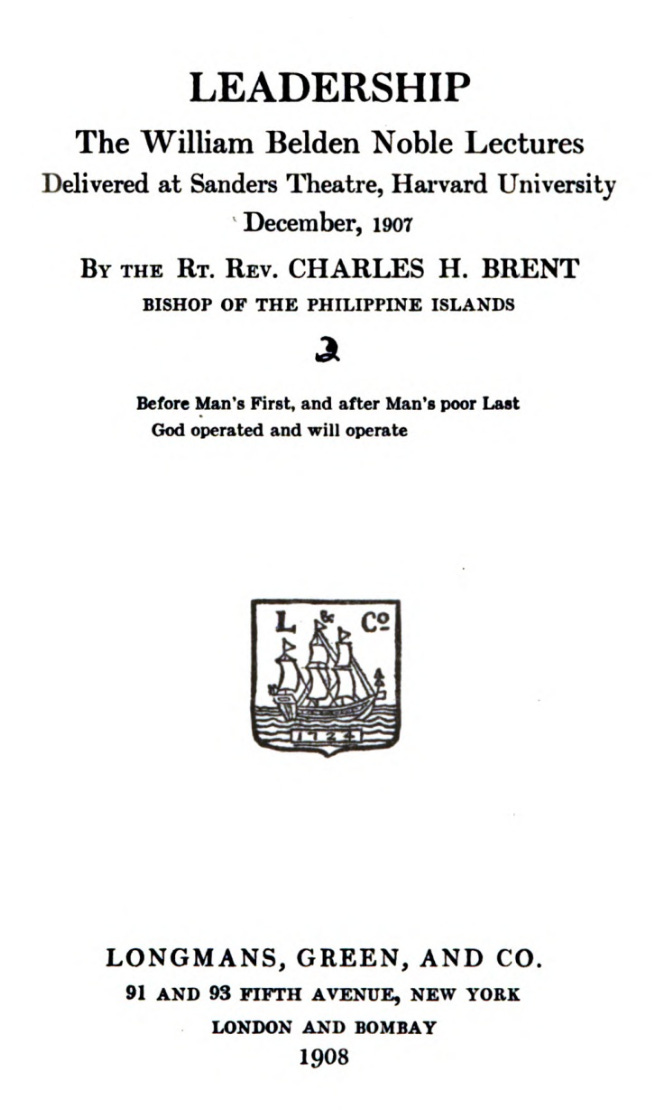

The deeper source of these personalistic methods was the rise across the Global North of large-scale corporations and managerial staffs, and the concomitant emergence of a new personal quality that officials across civil society, in an effort to manage these new behemoths, sought to identify and cultivate — “leadership.” This, not diversity, was the crucial term of discussion in university admissions offices at the advent of modern college admissions, and the top buzzword across the wider world of business and education from the 1900s to the 1930s.

“Diversity,” by contrast, only emerged as a significant term of art in higher education in the 1950s and 1960s. This chronology should not come as a surprise. In the United States, the 1920s, the era of the second Ku Klux Klan, immigration restriction, and widespread anti-Catholic bigotry against presidential candidate Al Smith, was the absolute nadir of diversity's intellectual wellspring, cultural pluralism. By contrast, the 1950s and 1960s, the era of the “Judeo-Christian tradition,” the end of WASP preferences in immigration, widespread admiration for the nation’s first Catholic president, not to mention the enormous successes of the Black Freedom Movement, saw cultural pluralism at its height. Invented to integrate Jews and other immigrants from eastern and southern Europe into the benefits of whiteness, cultural pluralism was rapidly repurposed throughout this period for much wider racial inclusion.

As competition for college admission intensified in the 1950s, officials looked for ways to rationalize the rejection of large numbers of students they otherwise would have been happy to admit. In “diversity,” administrators found a culturally ascendant discourse that spoke to multiple powerful constituencies, whether faculty, alumni parents, or sports fans who wanted to see linebackers from Idaho hitting hard on the field, and that could be used to justify rather arbitrary decisions to accept or reject otherwise similar white applicants. At first, the appeal of “diversity” had little to do with race, as college administrators in the 1950s made few attempts to increase non-white enrollment. Then, rather than an ironic reversal of diversity’s supposed origins in the 1920s, it was the discourse’s 1950s origins in a white-dominated form of cultural pluralism that allowed it to easily be repurposed in the 1960s for the inclusion of non-white students.

My argument, which I will elaborate over the coming weeks, is then as follows. Rather than a contingent consequence of ethnoracial conflict at Harvard and other elite institutions, the rise of highly personalistic selection standards at US universities in the 1920s is part of a much larger transformation of American society and political economy in the early twentieth century. Instead of an ideologically weak relic of the 1920s, diversity was the means by which the immense social systems that arose together with industrial modernity and Jim Crow in the early twentieth century were refashioned in the 1950s and 1960s for the purpose of limited racial inclusion.

This story has several advantages. Perhaps most importantly, it accounts for diversity’s surprising staying power, which must be acknowledged even in the face of the current Supreme Court’s sweeping campaign against a half-century of precedent. As with Roe, another case that stood for decades on a tissue of legal argument, we must account as much for Bakke’s survival as for its imminent doom. And as with Roe and “privacy,” Bakke's survival has been due to the way Justice Powell found in “diversity” an ideologically ambidextrous concept linked to ascendant values in American life.

Second, my story has the benefit that it can explain how “diversity” traveled from its origin point in a Supreme Court case that had nothing to do with the workplace to become the primary means by which to legitimize racial inclusion across American and, indeed, much of global society. Further, this story accounts for one of the great oddities in the history of higher education: why the American admissions system remains a global exception — just try discussing legacy or athlete preferences with anyone from abroad — while the US university system has become the global paradigm.

Finally, this story constitutes something of an entrée into a new history of the United States over the past 150 years. In this approach, I emphasize the operations of personal qualities like charisma and leadership as much as impersonal operations like bureaucratic tests and credentialing — not as parallel tracks but as two sides of the same coin.

The result is not yet another “great man history” but a story that explains how so many supposedly great men still manage to live rent free in our minds, whether captains of industry like Andrew Carnegie and Elon Musk or masters of scientific management like Frederic Winslow Taylor and Bill Smith. It is a history that tries to account for that uncanny sense that we are simultaneously living in Weber’s “iron cage” of bureaucratic rationalization as well as Marx’s endless series of “comprehensive and devastating crises.” An era of bureaucratic sludge and self-declared charismatic heroes; one of standardized tests and endless memoirs-cum-college-application-essays; defined by a form of capitalism as sclerotic as it is explosive — where we sit amid blocked arteries, awaiting the next stroke.

This is a long way from the Harvard case currently before the Supreme Court. But the only way to understand the origins of “diversity” is to track it back to the quality that diversity’s proponents — from deans of admission to the US military to the Supreme Court — have always insisted it serves: leadership.

There are roughly one thousand new history PhDs minted every year. As far as I can tell, the history of “leadership” largely remains to be written. Over the coming weeks, we’re going to be making a lot of history.

Stay tuned.

Complaint, Students for Fair Admissions, Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College, paragraphs 3, 5, 42-138, 148-167, 437, November 17, 2014.

Jerome Karabel, The Chosen (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005), 175-6, 178, 193, 592n53. Karabel cites a review essay on the 1920s origins of “diversity,” but the essay itself provides no such evidence.

None of these works are even acknowledged by the most prominent scholars to claim a connection between the Jewish quota of the 1920s and the diversity rationale of the 1950s and 1960s. The myopia of the scholarly literature on college admissions is remarkable.

Clyde Furst, “College Entrance Requirements,” The Educational Record 8 (October 1927), 308; Habib Kurani, Selecting the College Student in America (New York: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1931), 30-32.