Why Generational Thinking Isn't Bullshit

Reflections on Pavement, Don DeLillo, the very meaning of history, and the end of neoliberalism — plus, this week's links!

Welcome to Making History, a newsletter about how historians make history. In this installment, prompted by a Gen X colleague telling me he didn’t feel he was part of any generation, I write about my own experiences with “generational thinking” and explore the history and meaning of the very concept of generations.

Trigger warning: I spend maybe a bit more time than I should at the beginning of this post reading indie songs as keys to the collective unconscious. I promise: there is a pay-off. But if you didn’t spend several years of your life scrutinizing the lyrics of Stephen Malkmus, then you might be better off skipping to the headline below that reads “Jump to Here If Indie Rock Means Nothing to You.”

To subscribe, go here. It’s free!

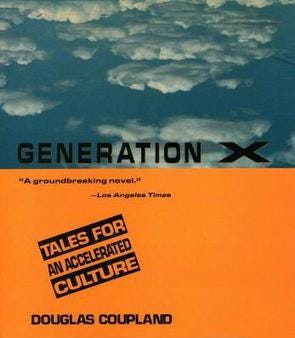

One of my less reputable historical interests is what better scholars refer to as “generational discourse.” As a geriatric millennial, a child of the early 1980s who grew up with landlines, dial-up modems, and desktop computers, and who got my first cell phone and Facebook account in the same year I graduated from college, 2005, I have often been intensely aware of my place in the middle of a generational divide. Unlike younger Millennials, I grew up with Gen X culture. My models for adulthood literally came from novels like Generation X (1991), which I read during my senior year of high school (2001) and saw as a map for my disaffected future, and Slacker (1991), which I watched my senior year of college (2005), and which seemed to offer a more promising checked-out yet dialed-in vision for my twenties and, one could dream, thirties and forties. This whole era of my life is perhaps best summarized by an exchange between my mom and my roommate during the week we graduated from college. “What are you going to do?,” my mom asked. His response, “About what?,” would have fit as well in 1985 and 1995 as in 2005.

When I first heard the definitive indie album of the era, Pavement’s Slanted and Enchanted (1992), I despised it as poorly recorded and basically meaningless. Yet I made it my project to learn to love the way Stephen Malkmus served as a kind of medium for every cultural mode of the era, channelling the generalized paranoia that appeared in a film like JFK (1991) or the aimless nostalgic attachment of a film like Dazed and Confused (1993) into lyrically content-less yet emotionally resonant songs like “Fame Throwa” and “Summer Babe (Winter Version).” Malkmus, and Gen X writ large, were the children of the first contemporary novel I really loved, White Noise (1985), where the Silent Generation father (DeLillo was born in 1936) listens intently as his daughter whispers during her sleep:

I was convinced she was saying something, fitting together units of stable meaning. I watched her face, waited. Ten minutes passed. She uttered two clearly audible words, familiar and elusive at the same time, words that seemed to have a ritual meaning, part of a verbal spell or ecstatic chant. Toyota Celica. A long moment passed before I realized this was the name of an automobile. The truth only amazed me more. The utterance was beautiful and mysterious, gold-shot with looming wonder.I know of no better description for all of Pavement’s best songs, whether “Zurich is Stained,” “Gold Soundz,” “Black Out,” “Frontwards,” or, a personal favorite, “Starlings of the Slipstream.” Inward emotion failed to find an adequate object with which to attach; emotion could thus only express itself through pervasive mass consumerism. When the child whispers, when Malkmus sings, the results are redolent with feeling, if empty of meaning.

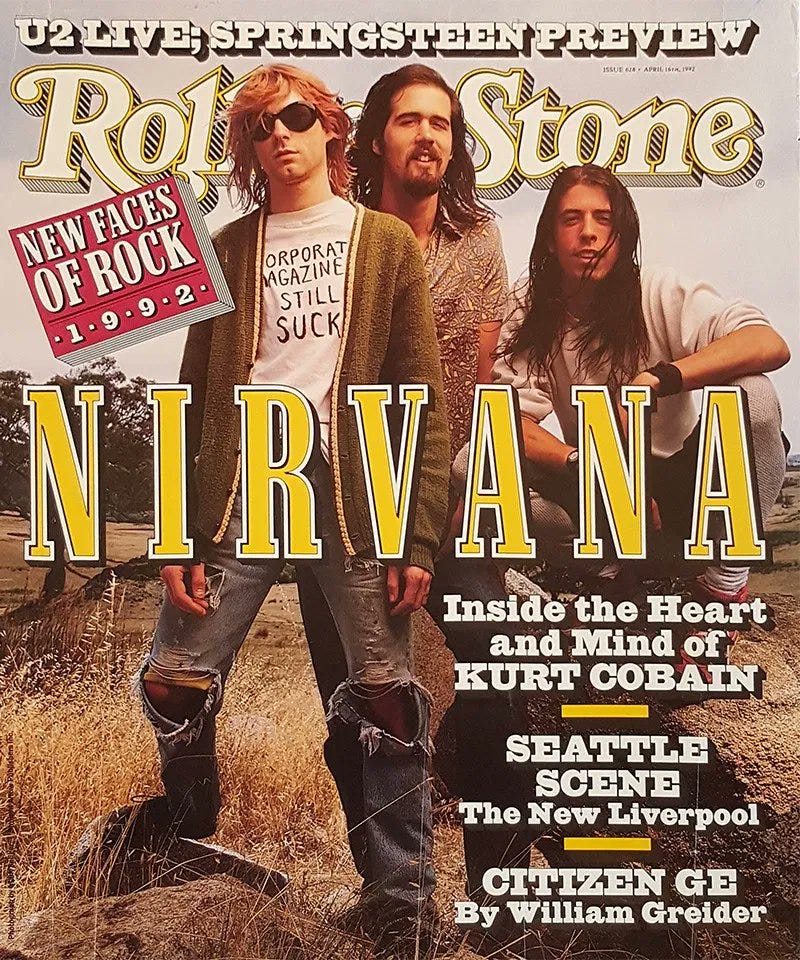

The result of this mindset was an ironic disconnect where emotion only found expression in the unendorsed stream-of-consciousness recapitulation of moments from pop culture — basically, Pavement’s lyrics. What was unimaginable was any kind of holistic connection between inner and outer worlds (short of the closed utopia of the hardcore scene). Hence the irremediable anxiety when “Grunge” went big. To be an authentic self and to make actual pop culture could only be a contradiction in terms. While Kurt Cobain did his best to respond to superstardom by donning a “corporate magazines still suck” T-shirt for the cover of Rolling Stone, Malkmus took the easier and more generationally characteristic route of dodging fame entirely with two classic self-sabotaging diss tracks that targeted his entire 1990s alt-rock cohort, “Cut Your Hair” and “Range Life.”

Jump to Here If Indie Rock Means Nothing to You

I bring all this up because of a conversation I had earlier this week with a fifty-something colleague in another department at Cornell. Somehow talk turned to the subject of generations and, although I generally find myself in agreement with my colleague’s political views, I was surprised to hear him say, “You know I never bought into any of that generational stuff; it just seemed like a bunch of Hallmark BS, basically marketing.” It would be hard to come up with a more characteristically Gen X response: if there’s a group, I’m not part of it — it’s nothing more than consumer culture, something you’re being sold, a pitch you can buy into or refuse entirely. As I joked on Blue Sky,

I promise I’m not making this up when I say my colleague was wearing a T-shirt that literally read “No Teams,” apparently a motto for his approach to his preferred sport, cycling.

With this kind of mindset, it’s easy to see why “Gen X erasure,” the compression of everyone older than Millennials into the Boomers, is so commonplace. Boomers define themselves by the 1960s; Millennials, by the 2010s. Gen X may have come of age in the 1980s and 1990s, but it is self-consciously a generation outside history, with a sense of self whose authenticity depends on never reaching for a more than ironic connection to its own time. At best a Gen Xer might long for a lost sense of living amid history — but that, of course, was the monopoly of the Boomers. As Thom Yorke sings on “The Bends” (1995): “I wish it was the Sixties, I wish we could be happy / I wish, I wish, I wish that something would happen.”

If Gen X knew anything, it was that they were a generation defined by “The End of History” (1989). In my experience, this is a self-understanding so pervasive that even those who disaffiliated from the general conservatism and individualism of their cohort, like my colleague, and embraced the radical politics of movements like Anti-Apartheid, Central American solidarity, and ACT UP, prefer all the more to conceive of themselves not against their generation but outside of generational discourse altogether.

As intellectual and cultural historians have shown, the very idea of the “generation,” like that of the “decade,” is little more than a century old. While there were earlier attempts to frame time in terms of neat ten-year periods, notably the 1890s, the first confirmed decade appears to have been the 1920s. To be sure, there were plenty of earlier turning points that divided one age cohort from another; I think of Talleyrand’s famous line, “He who has not lived in the eighteenth century before the Revolution does not know the sweetness of life.” But the idea that each successive age cohort amounted to a period in the history of the world reached its first full theorization with Karl Mannheim’s classic, “The Problem of Generations” (1923). The idea appears to be a byproduct of the rise of mass society, the onset of the Second Industrial Revolution, and, yes, the beginnings of marketing as a social scientific profession.

What I suppose I’m trying to suggest is that one of the chief signs of the neoliberal epoch’s power was the extent to which the generation that came of age at its apex, the 1980s and 1990s, lost a sense of itself as a social mass defined by shared experiences in the flow of history. There’s a lot of discussion just now among social theorists, historians, policy analysts, and even Biden Administration officials, about whether the neoliberal era is over. Only time will tell. But one thing that time has already told: When I came of age, I thought that I, too, would be part of a generation outside of time, with little affiliation to a larger group, let alone a sense of myself as taking part in the making of history. But if there is one thing that is true about Millennials, it is that we understand ourselves to make up a generation. Much of what that means began to become clear in the past decade — Occupy Wall Street and Black Lives Matter, Water Protectors and Starbucks organizers — but the historical mission of this generation, and the still more radical Zoomers whose footsteps we hear coming up from behind, still remains to be written.

Perhaps, as our Gen X friends might suggest, this embrace of generational discourse just means Millennials are easy marks, suckered by the simplistic history of Madison Avenue marketing. But as with so many of the cultural differences between Gen X and Millennials, I like to think my generation has got this right. Just as you can’t simply check out of capitalist social relations, you can’t check out of the consumer economy and the social groupings to which it gives birth. There’s hope for you yet, Gen Xers: you can still come to terms with your place in history; you can still remake the meaning of your generation. But you’ll have to start by giving in to the very idea of being a generation. Whether in terms of one’s own self-identity or that of one’s larger historical cohort, the only way out is in.

And now for this week’s links:

Are you ready for my History of Silicon Valley oral exam?

Corey Robin has a fantastic essay at the New Yorker on how the post-2016 liberal champions of “norms” came to embrace “norm breaking” like packing the Supreme Court.

The hottest thing in contemporary Marxism: the new Brenner debate, part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, and hot off the presses at New Left Review, part 5. I’ll be honest, I haven’t fully been keeping up, and a number of friends are involved, but as much as I respect Aaron Benanav I find I generally agree more in these matters with Seth Ackerman and Tim Barker. I look forward to diving in.

Manon Garcia’s The Joy of Consent: A Philosophy of Good Sex has just been released — very excited to read.

Distinguishing talent from hard-work in the making of meritocracy.

How did Texas Instruments, a supplier to the oil industry, become the co-inventor of the microchip? The hidden ties between oil and semiconductors.

Since you watched Stop Making Sense last week, you’re now ready for David Byrne’s full-length practice dance tape.

The most exciting book of 2024 will unquestionably be Aziz Rana’s The Constitutional Bind: How Americans Came to Idolize a Document That Fails Them. The first blurbs are in and this from Samuel Moyn gives an idea of the book’s significance: “This astonishing masterpiece divides the age that came before it from the new era that its appearance opens. … No more important book about the Constitution has appeared in a hundred years — if ever.” Pre-order your copy now!

In a way, what’s called Gen X culture is really more elder Millennial culture. By the early 90s when these key pieces of media you mention were produced, a good chunk of us Gen X types were already slipping around in adulthood. We may have produced these works, but we weren’t shaped by them in the same way those who encountered them as teenagers would have been.

The culture we grew up swimming in was undiluted Boomer culture. And we grew up witnessing that culture perpetually praise itself for its Flower Power era idealism while simultaneously embracing Reaganism. When the amount of self-mythologizing going on around you had everyone being their own Forrest Gump (there’s the obligatory Gen X pop culture reference for you) it’s probably not to hard to see how a suspicion of generational identity, and more importantly inherent generational virtue, begins to look suspicious.

And honestly, remain suspicious. When hearing how Gen Z will save us all, it’s not hard to recall when the same thing was said about the Boomers and how they then delivered us Reagan. Material change seems less assured when you notice Pride has started to look a lot like Flower Power.

There's both substantive and bull shitake versions of histories that attempt to capture the experiences of specific generations. On the substantive side are folks like Glen Elder on children of the Great Depression, or V.P. Franklin on children and youth of the Civil Rights Movement. On the questionable-but-plausible side are pop writers like David Kamp, of "Sunny Days," who argued that there was a zeitgeist of children's media culture in the early 1970s. My test of substance is whether someone who is interested in the cultural history of a generation tries to cross-check the cultural history with other parts of a generation's experience: for Gen X, for example, there's the expansion of special education and inconsistent but real expansion of desegregation in public schools; inflation and gas shortages during their childhood; a peaking of Cold War tensions in the late 1970s-early 1980s; the expansion of mass incarceration that disproportionately affected Black members of my generation; serious gun violence that peaked in our early adulthood. How that shaped our cultural experience is an open question, but some of that has to be in there, no?